Book presentation, Max Pinckers – „Red Ink“

This year the Belgian photographer received the 2018 Leica Oskar Barnack Award for his Red Ink series. Just a few weeks after the award ceremony, the book dedicated to the series was launched. We met up with Pinckers in the middle of the hustle and bustle of the Paris Photo photography fair with its countless book presentations and autograph signings. He was at the Polycopies stand where his book was being introduced. The floor was swaying, as the small side fair for special photo books was located, like in previous years, at a dock on the Seine river. Polycopies was the perfect setting for the initial introduction of the small but fine photo book, “Red Ink”.

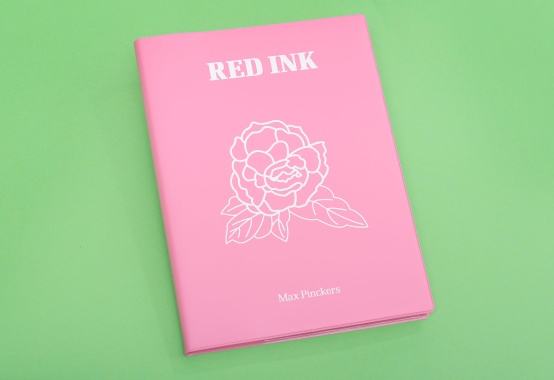

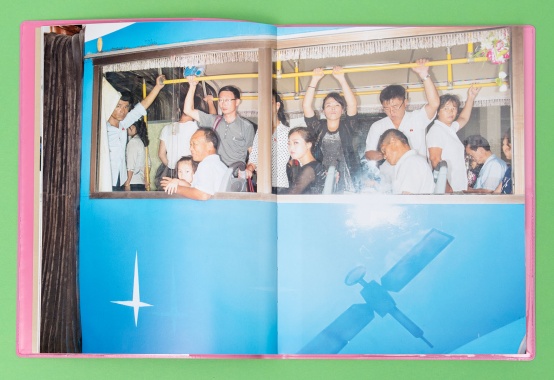

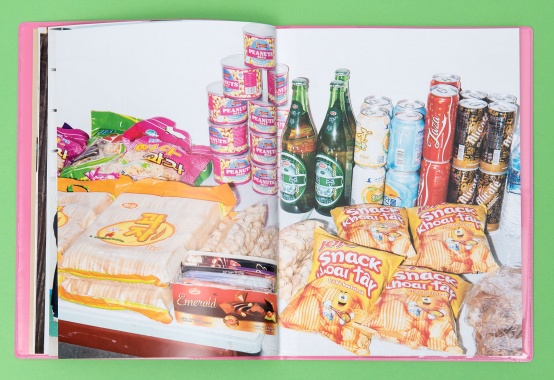

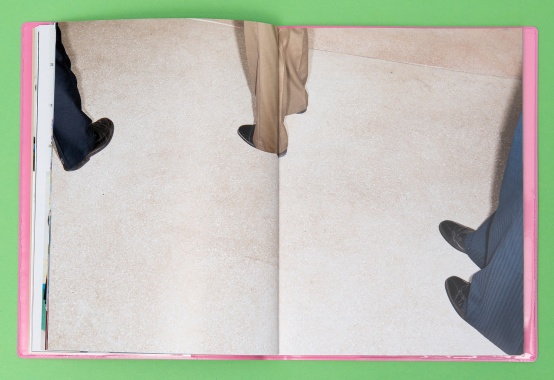

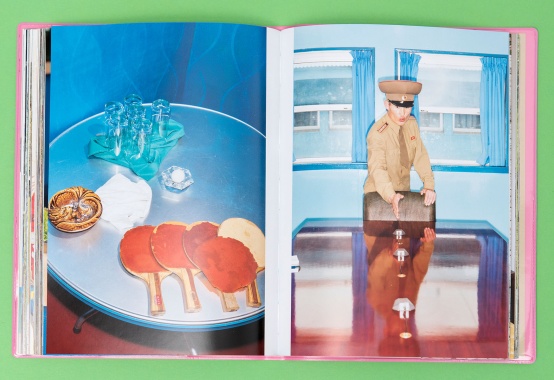

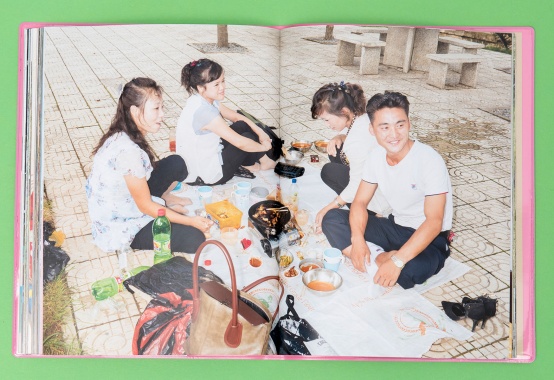

The book is wrapped in a pink-coloured dust cover made of plastic. As you browse through the pages, you will find yourself taking a garish journey throughout North Korea. In August 2017, together with his assistant Victoria Gonzalez-Figueras and the journalist Evan Osnos, Pinckers travelled to the country on assignment for The New Yorker. Up until then, only a few photo journalists had been granted permission to visit the hermetically-sealed country. Unrestricted reporting was out of the question: each location the three visited during their four-day stay, had been selected in advance, and they were constantly accompanied by official observers.

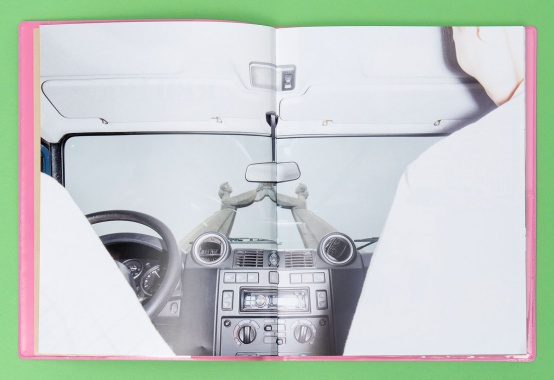

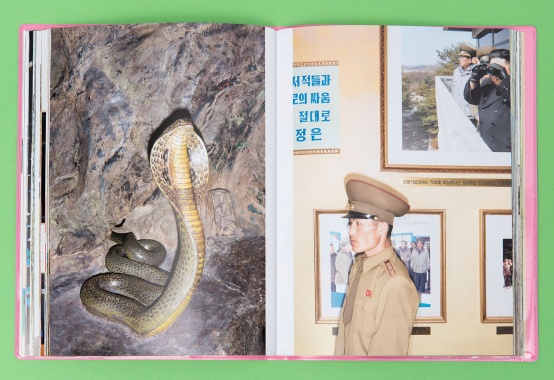

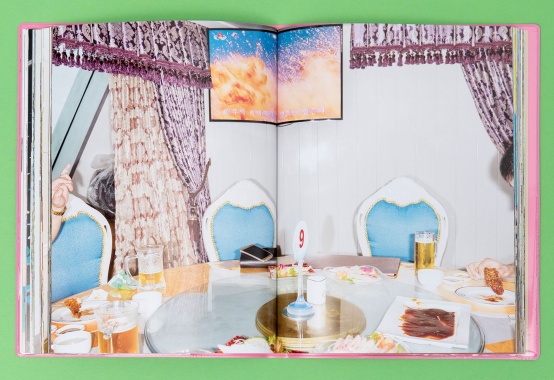

“Knowing that it would be impossible to reveal the reality behind the regime’s façade, I applied an aesthetic that refers to state propaganda and advertising, by using bold artificial lighting.”

The troubles already began in the early stages of the journey: the three had received their visas in Beijing, and the only step left was to get on their flight to Pyongyang; yet, their luggage was checked once more at security. Osnos describes the situation in the accompanying text: “At the final Chinese security post before boarding the plane, an officer examining the photography equipment withdrew a stack of battery packs, and pointed sternly to a sign: No lithium-ion batteries allowed. Max and Victoria were aghast. Losing the ability to use flash lighting would be like trying to write the article with only half the letters in the alphabet. We pleaded with the officer; we raged; we thought of offering a bribe. (We decided against it.) Nothing worked. At the final call for the flight, we gave up and scrambled aboard.” However, adversity is the mother of invention: while still in the plane, the photographer wired and stuck together a number of small flashes, so as to achieve an effect similar to that of a ring flash. This structure looked rather like a strange kind of horn on the camera, but it did do the job. This enforced construction also meant that he was considered less than a professional photographer.

The trip itself was carefully planned and staged by the hosts, with nothing left to chance; above all, a direct contact with the average North Korean person, or an authentic documentation of daily life, was to be avoided at all cost. Even so, the subversive potential of the 111 pictures that have been brought together for the book is immediately evident to the viewer. Through the blatant depiction of cold, garish perfection, the façades become brittle and questionable. The book is successfully in maintaining the balancing act between official documentation and subjective perception.

The title of the book refers to an old joke from former East German times, which the Slovenian philosopher and culture critic, Slavoj Žižek, adopted in his text “Willkommen in der Wüste des Realen” (Welcome to the Dessert of the Real). It says that a German worker headed off to a job in Siberia. As he expected there to be censorship, he agreed with his friends that any letters written in blue ink would be true, while any written in red would be untrue. Consequently, his first letter, written in blue ink, explained that everything in Siberia was wonderful, businesses were full, there was plenty of food, the apartment was large and warm, the women attractive and open, and western films were shown in cinemas. The only think impossible to find was red ink...

In his final summary Evan Osnos explains, “a trip to North Korea is only that — an experience of the senses, of the surface, of minor moments. It is a theatre of the mind. Ours was a glimpse of what it means to live in North Korea. We wait for the day when North Koreans can begin to tell the story for themselves.” By the way, his text is printed in blue.

MAX PINCKERS: RED INK

Texts by Evan Osnos and Slavoj Žižek

180 pages, 111 colour pictures, 20.5 x 15.0 cm, English, self-published

850-copy edition

Max Pinckers

Born in Brussels in 1988, the Belgian photographer uses his work to explore strategies of visual storytelling in documentary photography. He studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent from 2008 to 2012. Since then, Pinckers has published four books, and exhibited nationally and internationally many times. He founded Lyre Press publishers, and was previously a LOBA finalist in 2016 with his series Two Kinds of Memory and Memory Itself.