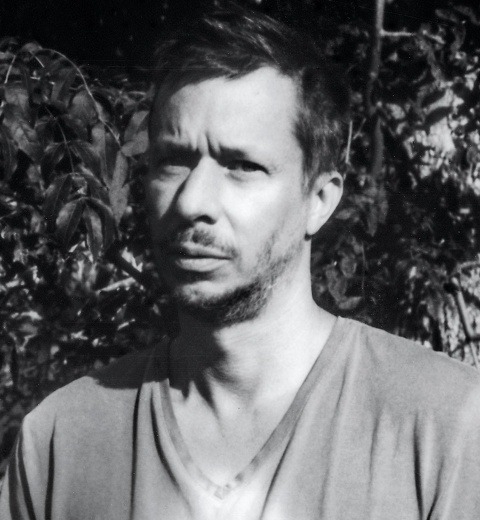

Interview Frank Hallam Day

Frank Hallam Day’s work focuses on people and nature, and the dysfunctional relationship between the two. The Leica Oskar Barnack Award winning series ‘Alumascapes’, shows how people use their RVs to escape civilization. One destination is Florida’s tropical forests; yet, the contrast between jungle and RV is extreme. The photographer questions the apparent longing for nature, which only seems possible while retaining the comforts of civilization. With intense lighting and specific colours, the contradiction becomes even more evident. In a setting somewhere between reality and fantasy, the RVs almost look like steel insects, with bright eyes illuminating the night sky. LFI asked the photographer about his series.

LFI: Do you own a caravan?

Frank Hallam Day: No … I might be tempted by an Airstream trailer – they are very lovely but very expensive. In American culture there is a subtle divide between RV owners who often live in the

suburbs or out in the country, and urban types like me.

LFI: What is the idea behind your ‘Alumascapes’ series?

Day: The relationship between man and nature has been a central theme in my work for several decades. Previously, my work depicted nature as deeply corrupted by human negligence, but in a stable, though degraded, end-state with mankind. This new body of work depicts a more sinister relationship.

LFI: Can you describe the process of making these pictures?

Day: First of all, I only work at night. Some of the pictures look like twilight, but it isn’t, it’s dark. I walk around in a promising area with the camera on the tripod over my shoulder and I have a bag of torches over the other shoulder – big ones, small ones, different kinds of bulbs in them, some warmer in color, some more blue. I try to work during the dinner hour, as RV owners, like everybody else, like to go out to dinner. Then I can work without their car in front of the RV, and get in a little closer without worrying so much. I always watch out for their return, however, and it certainly has happened. I take a shot with no lights to establish the correct exposure for the sky, then I add enough of my own light to complement that exposure value. If I have to illuminate a tree far away I reach for the biggest torch. The real problem is foliage close to the camera; it overexposes very easily. Then I shoot over and over again, examining the results on the LCD screen, until I think I have it. Or until the people come home.

LFI: Have you ever been discovered by the owners?

Day: Almost never. I am extremely nervous about this. There is an aspect of voyeurism and intrusion that is evident in the photographs, and I am sometimes in an awkward situation. But here’s the important point: during most of the time, the shutter is open (always 30 seconds, the longest exposure I can make without reading the manual), and my lights point up at the trees, because they are dark and absorb light. Light on the RV itself is almost never more than a few seconds, almost like an accidental brush with the light. So people coming by think I am trying to photograph owls up in the trees. But in truth, in the years I have been doing this, I’ve never seen an owl.

LFI: Why do you consider the stage-like effect of the images so important?

Day: These photographs are overtly theatrical; the foliage surrounding the vehicles resembles scenery props. The images are intended to look staged, almost dreamlike, half-way between fantasy and

reality. While it may seem they share the art world’s current wave of interest in the theatrical and the constructed, they are not staged. They are the product of months of travel in Florida using handheld lights and a tripod to capture the images. The occupants never know I’m there; their televisions are on and their blinds are drawn.

LFI: How much social criticism you see in the pictures?

Day: This, of course, is the whole point. There are many layers to this work, in the style and the content. Many of the images actually look nice, maybe even inviting, but to me the real importance

is in the subtexts of alienation and isolation from everything, from other people, and certainly from nature. And another point is the ambiguity of the situation. There is a kind of toxicity in

the scene, which interests me: what is the narrative behind this RV? Why is it here alone in the darkness? How did it get here? Are its inhabitants fleeing something? Has there been a calamity

reducing us to isolated aluminum life support pods in the forest? I am using these RVs for an artistic purpose which is actually rather disconnected from the reality of the people who live in them,

and their communities.

LFI: A special role is played by the specific dark in the images …

Day: … yes, for me a very important part of the photographs is what viewers may easily overlook: the utter, complete darkness in the distance. That to me is visceral and potent; it represents a

dangerous unknown beyond, in a world in which something seems to have gone very wrong. What is out there in the darkness? In post-production I make sure the darkness is indeed dark and featureless.

LFI: Do you see an American view in the series?

Day: The overtly voyeuristic creepiness of these pictures also evokes other topics: withdrawal from public space and engagement in American life, the obsessions of survivalists and the dominance over nature. In this sense, these RVs resemble the ultimate gated community: no community at all. Nothing is more American than an RV, but these pictures suggest other impulses underlying contemporary American reality: flight, concealment, isolation, bewilderment and withdrawal. The RVs sing the night song of the American dream, all the while spilling a toxic light into the jungle.

LFI: Will you continue the project?

Day: Probably yes, for another winter. I only work on these in the winter.

LFI: Thank you very much for this inspiring conversation.

Interview Ulrich Rüter

Frank Hallam Day

Born in 1948, living and working in Washington DC, USA. He has been active as a fine art photographer for many years. He has taught photography at Photoworks, at the Washington Center for Photography, and at the Smithsonian Institution. His work is in numerous museums and private collections in the US and abroad, including the State Museum of Berlin, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Portland Art Museum, and the San Diego Museum of Photographic Arts.