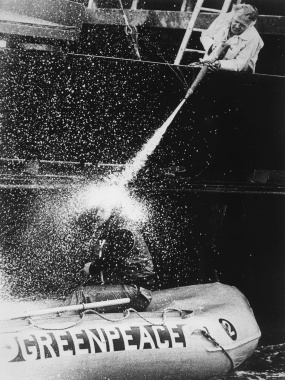

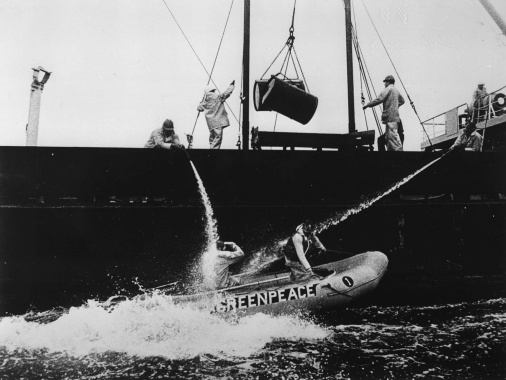

Floris Bergkamp – Greenpeace campaign against the dumping of nuclear waste, 1980

In 1980, the Leica Oskar Barnack Award was presented for the first time, as a special award within the framework of the international World Press Photo competition in Amsterdam. The jury decided on the breathtaking black and white motifs that Dutch photographer Floris Bergkamp captured, under life-threatening conditions, during a Greenpeace intervention.

David versus Goliath: on a stormy July evening in 1979, a group of small rubber boats faced off a freighter in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. The Greenpeace activists had set off from the environmental organisation’s mother ship, the Rainbow Warrior, to stop the British ship Gem from dumping further radioactive waste into the sea. The rubber boats sped across the water at speeds of up to 50 kilometres an hour. Using life-threatening manoeuvres, they repeatedly brought themselves directly under the larger vessel’s drop flap. The danger did not only come from the risks caused by the heavy swell: in addition to mocking them with scorn and derision, the crew aboard the Gem attacked the activists with powerful water cannons. The endeavour, directed at confronting the practices of radioactive waste disposal that were common at the time, seemed pretty hopeless.

Floris Bergkamp, 30 years old at the time, was in one of the rubber boats, documenting the dangerous undertaking from very close range. His comment on the situation is quite succinct: “I received the opportunity to accompany the environmental protection team on their mission – so I went along.” The risks involved only became apparent to him when the small boats reached the high seas; and once they were underway, he no longer had time to think too much about it. He photographed with one hand, while tensely trying to support himself with the other, so as not to end up overboard. It took a great effort to protect the camera from the sea spray; and changing the roll of film or the lens was a real challenge. Even in such circumstances, the photographer kept one clear goal in mind: not to miss one second of the courageous action, since he realised that he was documenting something that would otherwise remain hidden from the general public around the world.

“The photos I shot show exactly what happened on that occasion. If one of those barrels had fallen on the boys – who risked everything, by the way – there would have been a picture of it, too. It would have shown everybody, once and for all, what had happened.”

Industrial nations started carelessly dumping radioactive waste in the sea in the late 1940s. It was waste resulting from the production of nuclear weapons and from running power stations. In 1975, at a convention in London, an agreement was signed by most countries with nuclear capacities, acknowledging the concrete threat to the marine ecosystem from nuclear waste. Even so, there was a catch: the nuclear lobby succeeded in ensuring that so-called “low-level waste” was not affected by the agreement; and no one was really able to check the “harmlessness” of the barrels that continued to be dumped. Greenpeace began documenting the yearly trips of the Gem in 1978, without yet intervening directly. In the following year, they started using rubber boats and were able to carry out actions that had a dramatic effect on the public. To capture the proof and distribute it through the media, there was a British camera team on board, as well as the Dutch photographer. This resulted in authentic eye witness documentation. The wave of protests, initiated by Greenpeace, against the dumping of nuclear waste was to have an impact. The global sensitisation concerning the devastating polluting of the world’s oceans, was largely responsible for the complete prohibition, in 1993, of the disposal of radioactive waste in the sea.

The 1980 LOBA jury sent out a clear signal, when they granted the award to this series, defining the essential criteria for future competitions to “convincingly present the relationship between humanity and the environment in a complete picture series”. At the time, the award was not only an important recognition for the photographer; it also served to further spread the concerns of environmental activists. These concerns have not been fully dealt with, even today: there is still no documentation covering the type and degree of the radiation emitted by the sunken barrels; nor is it clear what damage the now dilapidated barrels may still be causing to the ecosystems of our oceans.

(Text written in 2020)

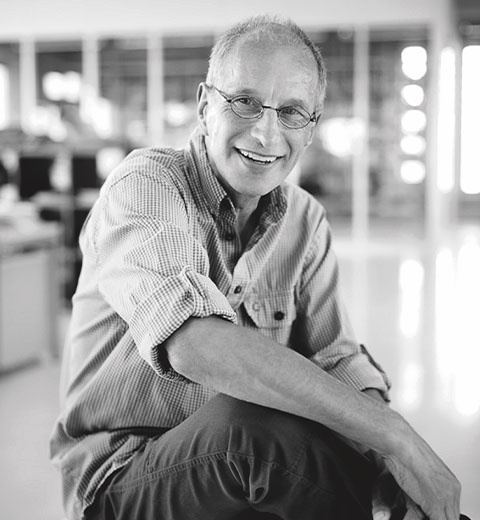

Floris Bergkamp

Born in Amsterdam in 1948, Bergkamp began studying tool construction, but then discovered photography and attended the Dutch Fotovakschool. As a photojournalist, the human aspect of his work was always his primary focus. In 1971, he began working as a freelance photographer in Alkmaar, in particular for the Nieuwe Revu, as well as other national and international magazines. He was a member of the press photo agency RBP Press and of Hollandse Hoogte. Bergkamp has been withdrawn from photojournalism for years now.