Wendy Watriss – The Implications of Agent Orange, 1982

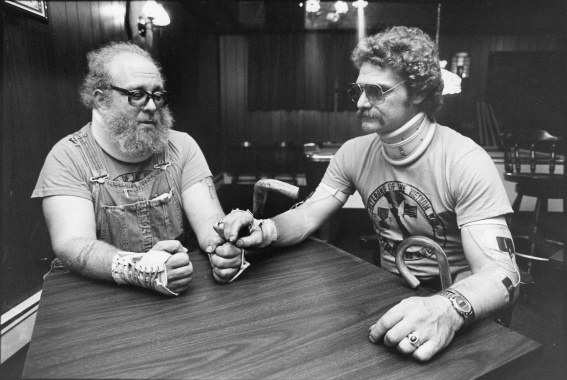

The photographer’s unflinching black and white pictures revealed the ruthless and devastating consequences to U.S. veterans, following the weaponised use of the herbicide called Agent Orange, during the Vietnam War. With her empathic portraits of participants in the war and their families, Wendy Watriss impressed the jury of the World Press Photo Awards at the time, and she was also the recipient, in 1982, of the third Leica Oskar Barnack Award.

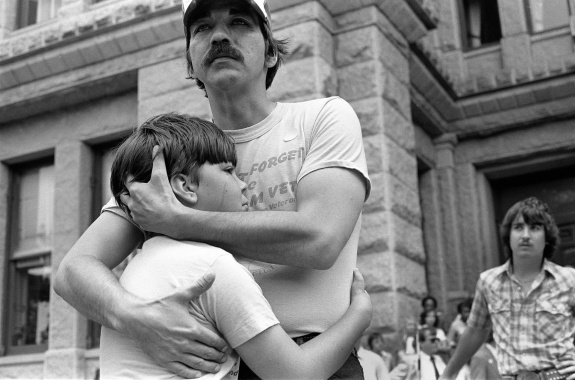

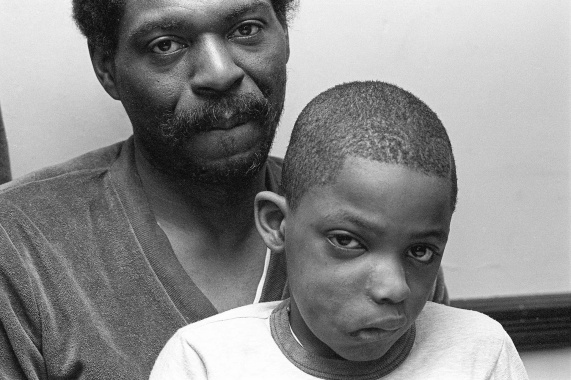

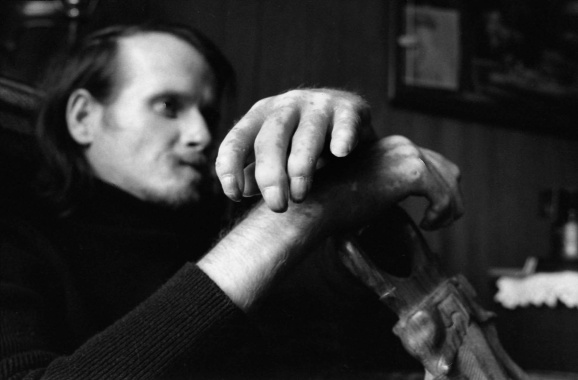

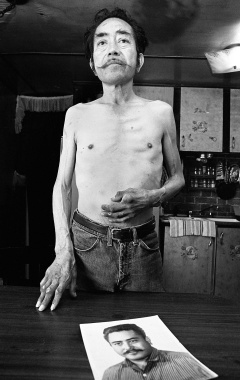

It was not only the veterans themselves who suffered from the delayed effects of the poison. Their children and families were affected as well. The dioxin in the herbicide, used as a weapon during the Vietnam War, was responsible for severe skin diseases, damaged livers, auto-immune problems, cancers, muscle loss, and other symptoms. Traces of the poison were evident in the children of veterans, who were often born with significant health problems and genetic deformities. For many years these realities were rarely discussed publicly. More often than not, information and truth were suppressed.

“LOBA also added credibility to my efforts to get state and national legislation passed to help Vietnam veterans. My having the LOBA award also encouraged a number of museums, universities and photography organisations to show the ‘Agent Orange’ series in the U.S. and abroad.”

Watriss’s work assumed an important role in this unfolding drama: Her series gave the many victims of Agent Orange a voice and visibility. Her work caused a sensation, because the challenging imagery captured in her pictures was extremely unsettling. After being seen in LIFE and in the Texas Observer, the photographs were quickly published around the world: Among other publications, they were picked up by the German magazine, Stern. Backed by her knowledge of the situation, Watriss became a fighter for the rights of the veterans and their families. Her social and political commitment was to leave its mark. Agent Orange was the military name for the product U.S. forces sprayed extensively from planes and helicopters during the Vietnam War, causing large-scale defoliation and destroying crops. The name came from the orange-coloured stripe used to identify the containers. The consequences were not only fatal for the Vietnamese people, but also for U.S. troops exposed to the poison.

When she was doing the research for her series, the biggest challenges the photographer faced were, first, finding the victims, and convincing them to allow their stories to be made public. Watriss remembers: “I told them I was doing a story that would show their suffering was real and their experience frightening. To tell the story, I was asking them to expose themselves and their vulnerabilities.” Her research gradually uncovered the extent of the impact of the poison. “The more I learned, the angrier I became. I had to build credibility and trust. As a civilian, it took knowledge, toughness, stamina, gentleness and the ability to project self-confidence. Above all, I needed to listen seriously.” The photographer’s pictures and research brought enough attention and recognition to the health issues and their consequences, that laws were introduced to initiate medical research and officially recognize these health problems as injuries of war, which enabled Vietnam war veterans affected by Agent Orange to be eligible for medical treatment. Her work continues to have an ongoing impact: The steps taken by activists at the time have later helped veterans from the Iraq and Afghan Wars, to organise and demand their rights.

“Because of the Oskar Barnack and World Press prizes, and what I have been able to achieve in practical ways to make change in the way chemical weapons are treated, this work has become an example of how to use documentary photography to achieve social change.”

The photographer captured the series with a Leica M and a Canon. Looking back, she sees it as one of the most important pieces from her entire body of work: “The ‘Agent Orange’ series is central to my life and my belief in the need to fight for social justice. This was emotionally difficult to do, because of all the pain and suffering of those who were central to the work. I could walk away, but they would live with it for a lifetime. They had to give so much of themselves in this process. Their courage is always a part of me. In some ways, my life is an invisible homage to them.”

(Text written in 2020)

“I often say that this kind of photography is not often a generator of change in and of itself. But it can be remarkably effective as a catalyst and a tool, if the photographer is ready to take the next step, organising and assembling the people and institutions that can make material change.”

Wendy Watriss

Born in San Francisco in 1943, Watriss grew up in Greece, Spain, France and the USA. She completed her studies at New York University with distinction; then worked as a newspaper reporter in Florida, and later as a producer of documentary films. She started working as a freelance author and photographer in 1970. In 1983, she co-founded FotoFest International in Houston, Texas, together with her partner, Fred Baldwin, and the German art historian, Petra Benteler. She managed and curated the event for many years. Watriss has been widely published and received numerous awards, including the Icon of Photography award from the National Society of Photographic Education. The archives of their personal photography will go to the Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas in Austin. The Menil Collection in Houston has an extensive collection of their individual and collective works.