Christopher Steele-Perkins – Learn to live with the thalidomide problem – 20 years afterwards, 1988

20 years after the biggest scandal of the pharmaceutical industry was uncovered, Christopher Steele-Perkins photographed some of the people who have to live with the consequences of that medical catastrophe. His series earned him the 1988 Leica Oskar Barnack Award.

They cut their wedding cakes or play billiards, using their feet. They sit in wheelchairs, get washed, and climb on horses, without arms to help them. Magnum photographer Chris Steele-Perkins took pictures, in the eighties, of victims of the thalidomide scandal; the images are shocking and impressive. We see people marked by deformities who, despite all the obstacles, are trying to master their lives. It was the worst medical scandal of the fifties and sixties. By the end of the fifties, when increasing numbers of children were being born without some of their limbs, the discussion speculated about a variety of causes; it was only in 1961 that doctors began to recognise a connection between the deformities and the tranquilliser produced with a synthetic active ingredient. During pregnancies, the medication, which had been on the market since 1957, was triggering serious damage to unborn babies. A total of 10,000 children came into the world with deformities. Thalidomide became synonymous with catastrophe.

“It is an honour to have your work recognised with the prestigious Leica Oskar Barnack Award.”

At the time, it was the Sunday Times that contributed significantly to bringing the pharmaceutical scandal to the awareness of the general public. Twenty years after the shocking events, while working for the Sunday Times, Steele-Perkins had the idea of doing a series on the victims. “I suggested to the editors that it would be interesting to show what had happened to some of the people who had been poisoned by thalidomide and had now become adults,” he remembers. The newspaper gave him the assignment, which became the cover story, and was also published by a variety of international papers. In 1988, “Learn to live with the thalidomide problem – twenty years afterwards” earned Steele-Perkins the Leica Oskar Barnack Award – “a great honour”, as he likes to say.

The colour pictures reveal very normal everyday lives: a family sitting on the sofa in their lounge; a bride and groom at the registry office; a man in a suit organising files; a mother feeding her child. The viewer becomes a witness to their reality, as though the camera was not even there. Work, office and home; hobbies, love and friendship. Nothing in the photographs appears planned or staged. “My photographic approach is observational,” Steele-Perkins explains. “I find out about the person, by talking to and spending time with them, and then encourage them to continue their life as if I was not there, taking photographs. With these photographs, I am not taking a directorial role, but rather letting them behave naturally.”

“Corporate and political abuse of the environment and of individuals continues in different ways – like climate change. I was showing how lives were affected by these abuses and, in some small ways, I continue to work on stories concerning these forms of exploitation.”

It is precisely this closeness and informality that makes the images so special and touching. They speak of the effort made by thalidomide victims to live life like other people – despite the scars and limitations they suffer. They have learnt to overcome the hurdles that are part of their existence, and to compensate for their deformities by other means. The viewer can sense their strong wills and characters, giving them the appearance of heroes. At the same time, the pictures criticise abuses of power and the dominance of consumerism. “Corporate and political abuse of the environment and of individuals continues in different ways – like climate change,” Steele-Perkins points out today. “I was showing how lives were affected by these abuses and, in some small ways, I continue to work on stories covering these forms of exploitation.” Even so, he does not think that he can change the world, as a result; yet, his voice resonates with the clamour for a better world.

(Text written in 2020)

“I don’t imagine I change the world; I sometimes add my voice to the clamour for a better world.”

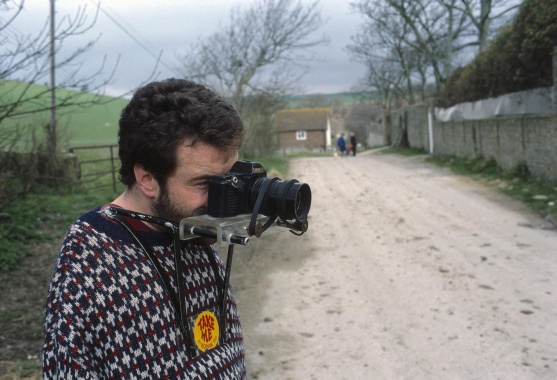

Christopher Steele-Perkins

Christopher Horace Steele-Perkins was born in Burma in 1947. He then grew up in Great Britain. After studying Psychology, he decided to work as a press photographer in London. He has been a member of the Magnum Photos Agency for over forty years, and his pictures have been delivering stories about British society for the same amount of time. A certain amount of his work, however, was produced during his numerous journeys – to places like Afghanistan, Japan and Africa.

Portrait: © Miyako Yamada