Interview with Wendy Watriss, who in 1982 was the first female photojournalist to win the Leica Oskar Barnack Award

Without a doubt, Wendy Watriss is one of the most renowned representatives of engaged photojournalism in the USA. At the same time, her name is indivisibly linked to the FotoFest International festival, that she co-founded back in 1983 in Houston, Texas, with her husband, Fred Baldwin, and the German art historian, Petra Benteler. During its 37 years of history, FotoFest has established itself as one of the world’s important of photo events. In 2020, due to the coronavirus pandemic, it had to be closed after just one week.

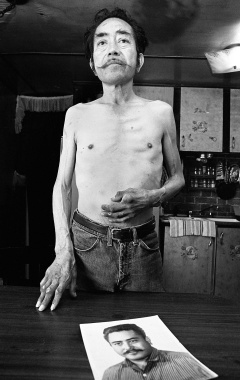

Watriss and Baldwin are considered a “power couple” within the US photo community. Because of their numerous responsibilities and commitments, they neglected their own photographic work frequently along the way. As a photographer, Watriss has been professionally linked to Leica for a long time. We spoke with her about her experiences and “The Implications of Agent Orange”, the series with which she won the 1982 Leica Oskar Barnack Award.

What was your personal motivation behind your series, “The Implications of Agent Orange”?

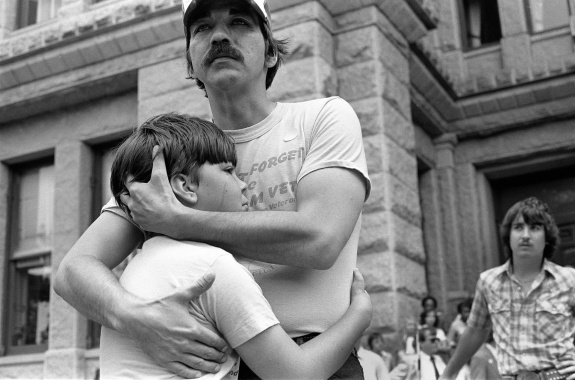

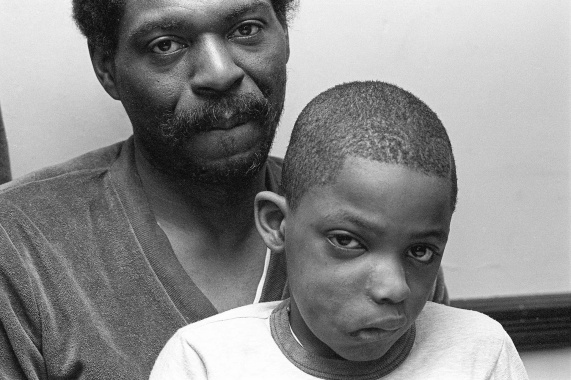

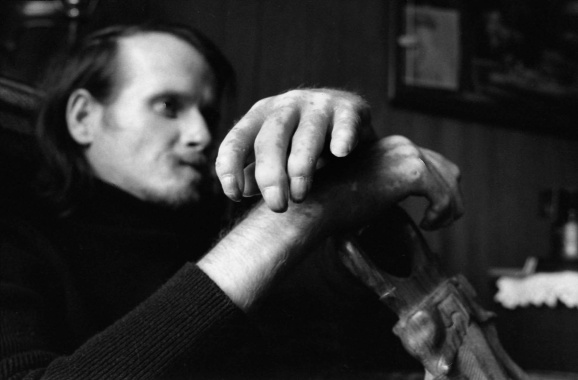

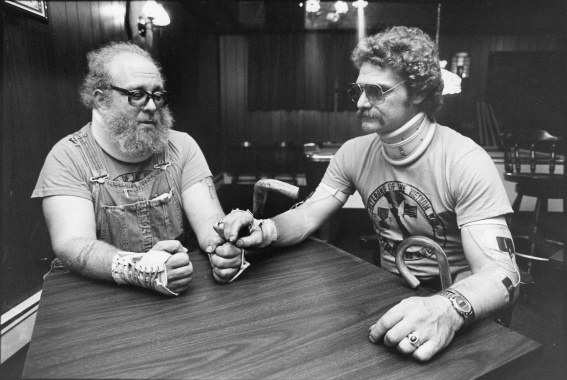

I was very opposed to the U.S. war in Vietnam. When I left newspaper reporting and television production to become a freelance photographer and writer in the early 1970s, I was looking for a way to work on the war that would expose its shortcomings and brutality. At the end of the 1970s I heard about how we were using the Agent Orange herbicide as a weapon of war. Very little had been publicized about it. U.S. Vietnam War veterans were trying to talk about it, but no one was listening.

I was still at the beginning of my career and I was very close friends with Gloria Emerson, a well-known, award-winning woman war correspondent. We talked about Agent Orange, and she gave me the name of an editor at LIFE magazine, which was still going strong as a publication at that time. John Larsen had been a correspondent in Vietnam and had seen the war close up. I proposed a story on Agent Orange and its impact on U.S. veterans. He was interested. “Take two months and begin to shoot it and then we will decide,” he said.

I did. Some of the early pictures of the Agent Orange series are among the strongest photographs I did for this series. I took these images back to LIFE, along with the voluminous research I had put together. Larson immediately said, “Yes, we will do the story.” They gave me nearly a year to do the work. They assigned a writer, but I never saw her. We worked separately. My pictures led the story. It was predominantly a photo story.

“Working alone as a woman at that time was not always easy. Women had just started to break into important positions in public media, and into male-dominated subjects such as reporting on war. I had to build credibility and trust.”

What were the biggest challenges at that time for you as a photographer?

As a civilian, it took knowledge, toughness, stamina, gentleness and the ability to project self-confidence. Above all, the ability to listen seriously. I am a very good investigator. I was very careful about choosing veterans who had a clear and direct exposure to Agent Orange. Their families suffered as well, women and children. The more I learned, the angrier I became. The women, wives of veterans and the mothers of their children, were the greatest help. They were angry too and not afraid of exposure.

How do you regard the importance of the series today?

This series has been very important in a number of ways. First, for veterans and the issue itself. I wanted to use the pictures to achieve social change, and they did. With the photographs, veterans and our legislative contacts, we were able to get widespread publicity and passage of Texas state legislation, to provide medical research and treatment for Agent Orange-related illnesses, and recognition of these health problems as war injuries. Then we went to Washington D.C. and the U.S. Congress. We did an exhibition in the Rotunda of the Capitol Building there. These actions, the story in LIFE magazine and the publicity of the awards brought national and international attention to the issue of Agent Orange, its effects on human life and the physical environment. The series is an example of how photography can be used to make real social change. I often say this kind of photography is not often a generator of change in and of itself; but it can be remarkably effective as a catalyst and a tool if the photographer is ready to take the next step, organizing and assembling the people and institutions that can make material change.

Looking back, what has LOBA meant for you and your on-going career?

It helped me get additional assignments from LIFE magazine and numerous other sources. I think it has added additional credibility to my standing in the field of photography as a whole. It was certainly an unintended catalyst for the creation of FotoFest. I won the Leica Oskar Barnack Award in 1982 and we incorporated FotoFest in 1983. After winning LOBA and World Press, Fred and I were invited to the 1983 Rencontres d’Arles, where we got the idea to start FotoFest and create a new international network of programs for photographers. Our idea was to create a platform for art and ideas that was open to the world and issues of social concern.

FotoFest International has spurred the creation of many similar, independent photography festivals around the world, and a global series of portfolio reviews for photographers that replicate the FotoFest model. The first FotoFest Biennial was in 1986. In the early 1990s, I began curating and managing FotoFest for the following 30 years. During this time, I did very little of my own photography. I have now begun to re-visit it.

What are you working on right now?

Many things at once. I am working with Russian curators on a book about the re-emergence of the creative voice in contemporary Russian photography, I am working on a curriculum for high school students on U.S. history and race relations based on a short film Fred and I did about our early photographic work in Texas. Fred and I are also working on a book on the story of our personal and professional relationship. We are planning to do a book on FotoFest. We have a two-year archive project for the Briscoe Center for U.S. History, a major research centre at the University of Texas, Austin. My work and Fred’s work, our personal and professional writing and photography, will be archived there with a major exhibition and publication. The Agent Orange series and material on the Leica Oskar Barnack Award will be there for future researchers and writers.

What would you like to advise young photojournalists and photographers today?

Despite the continuing uncertainties with the logistical and financial aspects of documentary photography, I think there are broad and exciting opportunities there. Passion and commitment are essential because it’s not an easy path. It’s very competitive within and between different media.

Wendy Watriss

Born in San Francisco in 1943, Watriss grew up in Greece, Spain, France and the USA. She completed her studies at New York University with distinction; then worked as a newspaper reporter in Florida, and later as a producer of documentary films. She started working as a freelance author and photographer in 1970. In 1983, she co-founded FotoFest International in Houston, Texas, together with her partner, Fred Baldwin, and the German art historian, Petra Benteler. She managed and curated the event for many years. Watriss has been widely published and received numerous awards, including the Icon of Photography award from the National Society of Photographic Education. The archives of their personal photography will go to the Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas in Austin. The Menil Collection in Houston has an extensive collection of their individual and collective works.