Emile Ducke – Kolyma – Along the Road of Bones

The Russian population’s memories of Kolyma are defined by fear. In this very remote region of eastern Siberia, hundreds of thousands of prisoners built a road, laboured in mines, and lost their lives. How does a society deal with its memories of the past? This was the question asked by the photographer Emile Ducke, who travelled along the 2000 km route, discovering traces left in the snow and on the faces of the people.

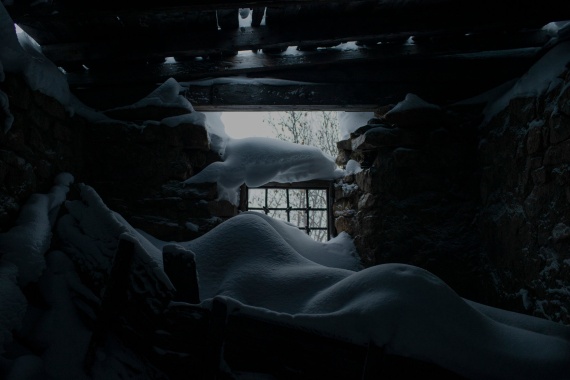

“Маска скорби”, the Mask of Sorrow, watches over Magadan – like a guardian of memories that shrouds the city with a veil of the past. This 15-metre-high, concrete monument is covered with faces, where tears seem to flow like they once did along the Kolyma Highway. Between 1932 and 1952, hundreds of thousands of victims of Stalin’s terror regime built a 2000-kilometre-long highway from Yakutsk to Magadan. It became notoriously known as the “road of bones” – a cemetery, bathed in the blood, sweat and tears of forced-labour camp inmates.

“With the fall of the Soviet Union, the economy in the Kolyma region collapsed and an exodus began. Now you find many abandoned settlements in the region, as the airline connections that once existed between them have been discontinued.”

“It was the Kolyma Tales, by the Russian author Warlam Schalamow, that inspired me to begin this project,” the photographer explains. “He used the book to process his own imprisonment in a forced-labour camp in the Kolyma region. He came to Magadan in 1937, a victim of Stalin’s Great Terror. I couldn’t forget his report on the ‘cold extreme of cruelty’. I wanted to understand how people in the region today deal with memories of the horrors of the Gulag.”

Wearing warm clothes, good gloves, and with sophisticated logistics, he set out in the deepest part of winter, when temperatures drop as far as minus 38 degrees Celsius. A common saying, back at the time, underlined the harshness of the Kolyma region’s climate: “Kolyma, you wonderful planet – twelve months of winter, and the rest is summer.” Ducke wanted his work to accurately reflect this cold. He was also aiming to document an area that today stands at a crossroad: the last witnesses of an era are passing away; the remains of the camps are disappearing in the snow.

“We always began each stretch very early, in order to reach the next place by the afternoon at the latest, and so as not to be the last people on the road. If you break down and don’t get any help, the danger of freezing overnight is very real.”

As he travelled along the Kolyma Highway, from Magadan to Yakutsk, he met former Gulag inmates, attended church services, and spoke with the last inhabitants of virtually abandoned settlements. They shared their stories with him, showed him faded old photos, and let him observe their daily lives. As a result, his images have become a conglomerate of what was and what is, of the past and the present, of pain and hope. “I witnessed how the descendants of inmates gathered under the Mask of Sorrow monument, and read out the names of the victims of the repression,” Ducke remembers. “In some settlements, the locals have set up small museums and memorials in remembrance of the region’s tragic past. One such place is Sussuman, where I photographed Mikhail Shibisty with the wooden cross that he erected next to the graves of former prisoners.” Even though nearly seventy years have passed since the gruesome acts of the Stalin era, the “Road of Bones” is still very present for the people of Kolyma, linking the distant past to their current lives. With sensitivity and poetry, and using a painting-like colour scheme, the photographer captures the traces of the disaster that have not yet been swept away.

“The nomination to the shortlist represents a tremendous recognition for my work. It’s a great feeling to see my photo essay among the impressive stories produced by the other photographers.”

Emile Ducke

Born in Munich in 1994, Emile Ducke has been living in Moscow for the past four years. He works on his own projects there, as well as on assignment for various international publications. He documented, for The New York Times, the consequences of the melting permafrost, and captured scenes of traditional daily life in Chechnya. Many of his photo essays have also appeared in the Washington Post, National Geographic, and Der Spiegel. He is the recipient of the n-ost Prize for his reporting on Eastern Europe.

Portrait: © Tamina-Florentine Zuch